Introduction

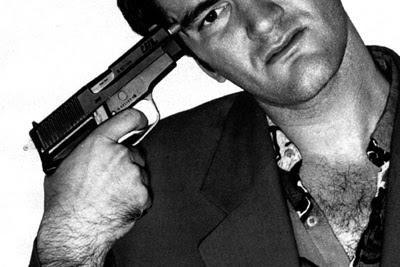

When Pulp Fiction hit the movie landscape like a tornado in 1994---the film surprised almost everyone by picking up a Palme d’Or at Cannes that year---it wasn’t only moviegoers lapping up writer/director Quentin Tarantino’s irresistible circular triptych of blood, guts, bullets and gleeful postmodern hip. Critics, by and large, bought into the hype for it too. When he reviewed it for the Chicago Sun-Times, Roger Ebert called Tarantino “the Jerry Lee Lewis of cinema, a pounding performer who doesn’t care if he tears up the piano, as long as everybody is rocking.” Owen Gleiberman of Entertainment Weekly called it “quite simply, the most exhilarating piece of filmmaking to come along in the nearly five years I’ve been writing for this magazine.”

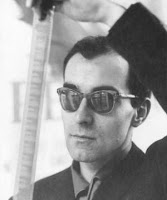

However, the most interesting critical reaction that came out of the Pulp Fiction bubble -- at least, the thing that caught my eye the most -- was voiced by David Denby, who wrote for New York magazine at the time. In his review of the film, Denby compared Tarantino not to Jerry Lee Lewis, but to the famous 1960s French New Wave auteur Jean-Luc Godard. According to Denby:

"Pulp Fiction is play, a commentary on old movies. Tarantino works with trash, and by analyzing, criticizing, and formalizing it, he emerges with something new, just as Godard made a lyrical work of art in Breathless out of his memories of casually crappy American B-movies. Of course Godard was, and is, a Swiss-Parisian intellectual, and the tonalities of his work are drier, more cerebral. Pulp Fiction, by contrast, displays an entertainer’s talent for luridness."

As a recent convert to the Jean-Luc Godard bandwagon myself, I admit that my initial reaction was to take Denby’s and others' critical declarations of this sort as proof of Tarantino’s inferiority to Godard as an artist. Sure, both directors share a lot of surface similarities: they both have certain stylistic likenesses, and they both dabble in the postmodern genre of self-reflexivity -- making movies that make you aware that you are watching a movie, to put it simply. But the differences are more telling: Godard, the cinema philosopher who likes to use popular American movie genres for his own intellectual and socially critical ends, seems to have totally different artistic priorities from Tarantino, the self-professed trash movie geek who often seems more interested in having fun with those same popular genres than in rigorously exploring anything political, semiotic or philosophical except in the most movie-based terms. A close look at Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction versus, say, Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964) and one could perhaps detect a sense of real world melancholy underlying the surface playfulness of Godard’s little heist picture that is hardly present amidst the unabashed pop trashiness of Pulp Fiction.

As a recent convert to the Jean-Luc Godard bandwagon myself, I admit that my initial reaction was to take Denby’s and others' critical declarations of this sort as proof of Tarantino’s inferiority to Godard as an artist. Sure, both directors share a lot of surface similarities: they both have certain stylistic likenesses, and they both dabble in the postmodern genre of self-reflexivity -- making movies that make you aware that you are watching a movie, to put it simply. But the differences are more telling: Godard, the cinema philosopher who likes to use popular American movie genres for his own intellectual and socially critical ends, seems to have totally different artistic priorities from Tarantino, the self-professed trash movie geek who often seems more interested in having fun with those same popular genres than in rigorously exploring anything political, semiotic or philosophical except in the most movie-based terms. A close look at Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction versus, say, Godard’s Band of Outsiders (1964) and one could perhaps detect a sense of real world melancholy underlying the surface playfulness of Godard’s little heist picture that is hardly present amidst the unabashed pop trashiness of Pulp Fiction. But then I got to wondering: could it just be that Tarantino and Godard are essentially the same filmmaker, except part of different time periods and totally different societies? Certainly, there are quite a number of noticeable differences between the France of the politically tumultuous 1960s -- when Godard was making his mark on world art cinema -- and the media-saturated, relatively more politically apathetic America of the 1990s, during which Tarantino first burst onto the scene with Reservoir Dogs (1992). Perhaps those who try to make a case for the artistic superiority of one director over another are, at least for the moment, forgetting that both directors come from such diverse backgrounds, and that all films speak of the contexts in which they are made and seen. Films, as do all works of art, do not exist in a vacuum, and to treat them as entities separate from time and space is to engage in only a superficial level of interpretation, at best.

But then I got to wondering: could it just be that Tarantino and Godard are essentially the same filmmaker, except part of different time periods and totally different societies? Certainly, there are quite a number of noticeable differences between the France of the politically tumultuous 1960s -- when Godard was making his mark on world art cinema -- and the media-saturated, relatively more politically apathetic America of the 1990s, during which Tarantino first burst onto the scene with Reservoir Dogs (1992). Perhaps those who try to make a case for the artistic superiority of one director over another are, at least for the moment, forgetting that both directors come from such diverse backgrounds, and that all films speak of the contexts in which they are made and seen. Films, as do all works of art, do not exist in a vacuum, and to treat them as entities separate from time and space is to engage in only a superficial level of interpretation, at best.I think that this is an important distinction to make, especially when it brings into clearer focus the fact that both directors, to admittedly varying degrees, are working in basically the same tradition of the self-reflexive work of art, a tradition that goes all the way back to Cervantes and even Shakespeare -- with its self-consciousness and its implicit allegory of readership -- and maybe beyond. So while Godard is always aware of the social function of the cinematic image, Tarantino turns self-reflexivity into a form of genre pastiche. Does that automatically make one director’s work more important than the other? Godard fans might prefer his social analysis and critique to the self-absorbed playfulness of Tarantino, but what explains Tarantino’s immense popularity all over the world on the basis of Pulp Fiction or his recent two-part trash epic Kill Bill (2003, 2004)? Godard, by comparison, may command only an intense cult following outside France at best, particularly now that he has remained fairly reclusive over the past couple of decades. One would certainly not see recent Godard works like In Praise of Love (2001) or Notre Musique (2004) headlining the marquees of big multiplexes nationwide.

Thus, in this weeklong series -- and in celebration of both Film Forum's revival of Godard's La Chinoise starting Wednesday and the recent DVD release of Tarantino's Death Proof -- I would like to examine the similarities and differences between Godard and Tarantino in many of their different facets. I plan to explore this comparison not only by examining their respective work and comparing and contrasting them, but also by considering both directors in terms of both their personal biographies and objective historical contexts. I will then draw on all this to evaluate how both directors are similar yet temperamentally and substantively different, and how each is representative of his particular era and social environment. As for their body of work: because Godard has been so prolific for over four decades now, it would simply be unwieldy to try to encompass his entire body of work (a lot of which isn’t even readily available on video). For that reason, I will focus almost entirely on the bulk of his groundbreaking oeuvre from the 1960s -- his most popular period, arguably, and the one most comparable to Tarantino’s -- when comparing it to Tarantino’s comparably meager, yet equally varied and fascinating output.

Thus, in this weeklong series -- and in celebration of both Film Forum's revival of Godard's La Chinoise starting Wednesday and the recent DVD release of Tarantino's Death Proof -- I would like to examine the similarities and differences between Godard and Tarantino in many of their different facets. I plan to explore this comparison not only by examining their respective work and comparing and contrasting them, but also by considering both directors in terms of both their personal biographies and objective historical contexts. I will then draw on all this to evaluate how both directors are similar yet temperamentally and substantively different, and how each is representative of his particular era and social environment. As for their body of work: because Godard has been so prolific for over four decades now, it would simply be unwieldy to try to encompass his entire body of work (a lot of which isn’t even readily available on video). For that reason, I will focus almost entirely on the bulk of his groundbreaking oeuvre from the 1960s -- his most popular period, arguably, and the one most comparable to Tarantino’s -- when comparing it to Tarantino’s comparably meager, yet equally varied and fascinating output. Ultimately, the broad question I would like to pose is: is Tarantino really a Jean-Luc Godard of the 1990s and today? Maybe there is something to the comparison after all, and not just technically or stylistically speaking. If Godard is a reflection of a politically-conflicted, self-aware, industrializing society, Tarantino is perhaps an example of Godard’s convictions taken to a perversely logical conclusion. In a society that has already been industrialized and invaded by pop culture as America has, maybe it is only logical that a Tarantino would take that self-awareness and popularize it for the mass American audience -- an audience, some might say, that prefers its entertainment to be pure escapism, something that Tarantino provides even as he occasionally makes gestures toward something deeper. And what of Tarantino’s worldwide popular success compared to Godard’s relatively provincial success? What does that suggest about the societies and audiences from which both filmmakers came? And, if they are so different, does that necessarily mean that they are both incomparable? Or could it just mean that Tarantino is a kind of Godard stripped of political content (and perhaps creating an implicit stance of its own: apathy) and raised on a diet of both high art and pop culture?

Ultimately, the broad question I would like to pose is: is Tarantino really a Jean-Luc Godard of the 1990s and today? Maybe there is something to the comparison after all, and not just technically or stylistically speaking. If Godard is a reflection of a politically-conflicted, self-aware, industrializing society, Tarantino is perhaps an example of Godard’s convictions taken to a perversely logical conclusion. In a society that has already been industrialized and invaded by pop culture as America has, maybe it is only logical that a Tarantino would take that self-awareness and popularize it for the mass American audience -- an audience, some might say, that prefers its entertainment to be pure escapism, something that Tarantino provides even as he occasionally makes gestures toward something deeper. And what of Tarantino’s worldwide popular success compared to Godard’s relatively provincial success? What does that suggest about the societies and audiences from which both filmmakers came? And, if they are so different, does that necessarily mean that they are both incomparable? Or could it just mean that Tarantino is a kind of Godard stripped of political content (and perhaps creating an implicit stance of its own: apathy) and raised on a diet of both high art and pop culture? Self-Consciousness

Self-ConsciousnessAt one point in Band of Outsiders, all three main characters -- Franz (Sami Frey), Arthur (Claude Brasseur) and Odile (Anna Karina) -- impulsively decide to share a minute of silence amongst one another because, as Franz says, they don’t have anything left to say to each other at that particular point. When they do initiate their minute of silence, however, Godard suddenly silences the soundtrack as well -- almost as if Godard wants you to feel in your gut just how long a minute of silence can really be.

In Pulp Fiction, when Mia Wallace (Uma Thurman) responds to Vincent Vega’s (John Travolta) befuddlement (“What the fuck is this place?”) after they both get to Jackrabbit Slim’s, Mia coaxes him by saying “Don’t be a…” and then drawing a rectangle in the air to visually denote “square.” But when she draws that rectangle, Tarantino visually emphasizes it so that she seems to be drawing an actual physical rectangle -- one made up of tiny brightly-lit bulbs -- onscreen.

Both of these moments have the effect of breaking the fourth wall, of deliberately throwing us out of the movie for that one brief period of time -- in effect, to remind us that what we are watching is a movie. In other words, those two examples evince self-consciousness about their artistic selves that courses through not only both films, but also through both directors’ bodies of work as a whole. Furthermore, it is this tradition of self-consciousness in which both Godard and Tarantino consistently work -- it is, in a broad sense, what is so strikingly similar about both directors.

First things first: what makes up a “self-conscious” work of art? A self-conscious work of art signifies a work that consistently makes the audience aware of its sheer movie-ness (to put it in fairly crude terms). Many fiction films demand that audience members assent to the illusion that the filmmakers -- the director, the actors, the behind-the-scenes crews -- are presenting to us. For that reason, classical Hollywood films are known for their unobtrusive style: invisible editing, carefully-structured plotting, and well-placed camerawork, among other attributes. Better to use cinematic materials to tell the story well rather than experiment too much and risk impairing our willing suspension of disbelief.

First things first: what makes up a “self-conscious” work of art? A self-conscious work of art signifies a work that consistently makes the audience aware of its sheer movie-ness (to put it in fairly crude terms). Many fiction films demand that audience members assent to the illusion that the filmmakers -- the director, the actors, the behind-the-scenes crews -- are presenting to us. For that reason, classical Hollywood films are known for their unobtrusive style: invisible editing, carefully-structured plotting, and well-placed camerawork, among other attributes. Better to use cinematic materials to tell the story well rather than experiment too much and risk impairing our willing suspension of disbelief.Self-conscious artists, however, are less interested in immersing their audience in their films’ illusions than in exposing the gears underlying those illusions, in making us aware of how fake those illusions actually are. Look, self-conscious filmmakers seem to say to their audience, I could tell this story in the familiar classical manner. I could make more of an effort to immerse you in the lives of these characters and the world they inhabit. But that would only be false to reality, because classically-told stories simply aren’t real, as much as we might want to believe they are. As Robert Stam puts it:

"In their freedom and creativity, anti-illusionistic artists imitate the freedom and creativity of the gods. Like gods at play, reflexive artists see themselves as unbound by life as it is perceived (Reality), by stories as they have been told (Genre), or by a nebulous probability (Verisimilitude). ... The god of anti-illusionist art is not an immanent pantheistic deity but an Olympian, making noisy intrusion into fictive events. We are torn away from the events and the characters and made aware of the pen, or brush, or camera that has created them."

If art is all about raising our consciousness of the world around us, of looking at certain previously-taken-for-granted things anew, self-conscious works of art use, as their playing field, previous works of art instead of something from the outside world. Self-conscious artists take apart what has already been done before, try to understand what previous artists were trying to do with those elements and how they went about doing it, and put all those elements back together again to create something new.

Stam notes that this approach has roots all the way back to Shakespeare; he cites the use of the play-within-a-play in Hamlet as an early example of self-reflexivity even before Cervantes picked it up and pushed it further in Don Quixote. Only relatively recently, however, has this kind of approach been taken seriously as an artistic style in the cinema.

Stam notes that this approach has roots all the way back to Shakespeare; he cites the use of the play-within-a-play in Hamlet as an early example of self-reflexivity even before Cervantes picked it up and pushed it further in Don Quixote. Only relatively recently, however, has this kind of approach been taken seriously as an artistic style in the cinema.Both Quentin Tarantino and Jean-Luc Godard fit right into this mold of the postmodern self-conscious artist. Their works deliberately take you out of your involvement in the film’s story and point up the artificiality of the construct. Though their purposes for doing so may be different (as we will see later on), their means are often surprisingly similar.

Reworking classical narrative

Neither Godard nor Tarantino show much interest in telling stories in any conventional sense. Indeed, Godard -- in films like Masculin féminin (1966), Two or Three Things I Know About Her (1967) and Weekend (1968) -- barely shows any interest in telling any kind of story at all, instead preferring to essentially make either portrait films (his fascinated-yet-critical look at French youth and the sexual divide in 1960s France in Masculin féminin, for instance) or essay films (his seemingly stream-of-consciousness philosophical ruminations on the power of the image in an increasingly industrialized Paris that form the backbone of Two or Three Things). Godard’s deliberate disregard for classical narrative convention goes all the way down to the level of technique, most notably editing (his celebrated use of jump cuts and mismatched shots from Breathless (1960) on) and sound (his playful experiments with music and sound in A Woman is a Woman (1961) or his random dropping-out of sound at certain points in Band of Outsiders and Masculin féminin).

On the other hand, Tarantino often sticks to a fairly unobtrusive technical style. Much like Godard, he is an actor’s director, sometimes preferring long takes to allow his actors to strut their stuff, other times cutting back and forth between actors who are conversing with each other. Tarantino’s innovations of narrative are temporal rather than technical. Pulp Fiction is known for its circular, three-story plot structure, in which the film starts and ends in the same setting; in which a threatening incident in an apartment cuts away in media res only to resume in the third story; and in which a major character killed off in the second story returns very much alive in the third story, which had taken place beforehand. Reservoir Dogs and the Kill Bill films all play with this kind of non-chronological storytelling -- the former in particular cuts back and forth between past and present in dissecting how a robbery attempt went horribly wrong. Even Tarantino’s most linear film, Jackie Brown (1997), has one show-stopping sequence -- a homage to Stanley Kubrick’s early heist thriller The Killing (1956) -- that replays a theft from three different points of view. And his most recent film, Death Proof (2007), still manages a measure of structural rigor even while remaining linear all the way through: it’s a two-part work, with rhyming motifs giving it an underlying sense of unity.

On the other hand, Tarantino often sticks to a fairly unobtrusive technical style. Much like Godard, he is an actor’s director, sometimes preferring long takes to allow his actors to strut their stuff, other times cutting back and forth between actors who are conversing with each other. Tarantino’s innovations of narrative are temporal rather than technical. Pulp Fiction is known for its circular, three-story plot structure, in which the film starts and ends in the same setting; in which a threatening incident in an apartment cuts away in media res only to resume in the third story; and in which a major character killed off in the second story returns very much alive in the third story, which had taken place beforehand. Reservoir Dogs and the Kill Bill films all play with this kind of non-chronological storytelling -- the former in particular cuts back and forth between past and present in dissecting how a robbery attempt went horribly wrong. Even Tarantino’s most linear film, Jackie Brown (1997), has one show-stopping sequence -- a homage to Stanley Kubrick’s early heist thriller The Killing (1956) -- that replays a theft from three different points of view. And his most recent film, Death Proof (2007), still manages a measure of structural rigor even while remaining linear all the way through: it’s a two-part work, with rhyming motifs giving it an underlying sense of unity.The point here is that neither director makes films that fall neatly into typical Hollywood storytelling structures, even though both directors unapologetically dabble in well-worn Hollywood genres. This has the effect of taking a viewer out of his/her Hollywood-induced comfort zone as far as storytelling is concerned.

References

The films of both Godard and Tarantino are often layered -- or littered, depending on whom you ask -- with references: to pop culture, politics, other films, popular music, literature, etc. Take Godard’s crime films, like Breathless and Band of Outsiders: they are full of references to both literature (the Dolores Hitchens novel that Godard credits as the inspiration for Band of Outsiders is referenced visually and verbally in the film; one of the characters is named Arthur Rimbaud) and cinema (the poster of Humphrey Bogart that seemingly stares at Michel in Breathless; the use of legendary filmmaker Fritz Lang playing himself in the film-about-filmmaking Contempt (1963); the paraphrasing of narration from Fritz Lang’s 1950 thriller House by the River to alert “latecomers” to the theater at one point in Band of Outsiders); later films such as Pierrot le fou, Masculin féminin and Weekend would also add explicit and implicit allusions to the contentious political events of the day -- Vietnam in particular -- to his burgeoning plate of references. (But then, even the relatively lightweight Band of Outsiders finds Godard in a serious-enough mood to make a random yet poignant reference to Rwandan atrocities as Franz is reading the newspaper out loud at one moment.)

The films of both Godard and Tarantino are often layered -- or littered, depending on whom you ask -- with references: to pop culture, politics, other films, popular music, literature, etc. Take Godard’s crime films, like Breathless and Band of Outsiders: they are full of references to both literature (the Dolores Hitchens novel that Godard credits as the inspiration for Band of Outsiders is referenced visually and verbally in the film; one of the characters is named Arthur Rimbaud) and cinema (the poster of Humphrey Bogart that seemingly stares at Michel in Breathless; the use of legendary filmmaker Fritz Lang playing himself in the film-about-filmmaking Contempt (1963); the paraphrasing of narration from Fritz Lang’s 1950 thriller House by the River to alert “latecomers” to the theater at one point in Band of Outsiders); later films such as Pierrot le fou, Masculin féminin and Weekend would also add explicit and implicit allusions to the contentious political events of the day -- Vietnam in particular -- to his burgeoning plate of references. (But then, even the relatively lightweight Band of Outsiders finds Godard in a serious-enough mood to make a random yet poignant reference to Rwandan atrocities as Franz is reading the newspaper out loud at one moment.)Tarantino tends to limit his references simply to cinematic ones -- movies were the biggest part of his upbringing after all, as we shall see later -- but Roger Ebert does note one interesting literary allusion: “the opening exchange between Jules and Vincent about what the French call Quarter-Pounders, for example, is a reminder of the conversation between Jim and Huckleberry Finn about why the French don’t speak English.” As he does with movies, Tarantino is taking a literary trope from a classic American novel and updating it on film for a newer audience. Also interesting to note are Tarantino’s references to Godard himself. In the unrated version of Death Proof, for instance, one lengthy sequence that kicks off the film’s second half is shown in black-and-white until the film suddenly reverts back to color, in a piece of technique that may remind some viewers of Godard’s switching of color filters in an opening sequence of Contempt. Or consider the twist sequence in Pulp Fiction, which recalls the Madison dance sequence of Band of Outsiders in its randomness and sense of isolation. Uma Thurman in Pulp Fiction is also done up like Anna Karina in My Life to Live (1962), short black hair and all, even if Mia Wallace comes off more like a gangster’s wife playacting at being a gun moll than Karina’s Nana ever does throughout Godard’s film. (In some cases with Tarantino’s references, context matters less than the fact that he makes the reference in the first place.)

But such references often aren’t simply mere mentions or hints of that sort. Often, Godard and Tarantino run deeper, trying to allude to whole genres or styles with their references. Godard’s voiceover narration of Band of Outsiders is full of comparisons: when Arthur decides to delay the robbery, Godard says that such an act is “in keeping with the tradition of bad B movies”; when Franz decides to turn around to try to save his friend, he’s compared to “the hero of a legendary romance.” (Ironic, because Band of Outsiders, though it may seem like a similar kind of bad B movie or legendary romance when you hear a plot description, certainly doesn’t play like either; if anything, it is a romantically anti-heroic film that often alludes to a heroic tradition.) Even his characters diegetically evoke such movie-conscious associations: Arthur thinks of Franz as “a good shield…like in the movies”; one random character asks his teacher how to translate “a big million-dollar film” to English.

But such references often aren’t simply mere mentions or hints of that sort. Often, Godard and Tarantino run deeper, trying to allude to whole genres or styles with their references. Godard’s voiceover narration of Band of Outsiders is full of comparisons: when Arthur decides to delay the robbery, Godard says that such an act is “in keeping with the tradition of bad B movies”; when Franz decides to turn around to try to save his friend, he’s compared to “the hero of a legendary romance.” (Ironic, because Band of Outsiders, though it may seem like a similar kind of bad B movie or legendary romance when you hear a plot description, certainly doesn’t play like either; if anything, it is a romantically anti-heroic film that often alludes to a heroic tradition.) Even his characters diegetically evoke such movie-conscious associations: Arthur thinks of Franz as “a good shield…like in the movies”; one random character asks his teacher how to translate “a big million-dollar film” to English.Tarantino does something similar -- taking recognized genre characteristics and putting them into entirely new situations -- except his references simply stay on the level of iconography. Thus, Pulp Fiction doesn’t so much impose genre conventions onto grounded characters as basically conceive characters as icons from the start and then fashion them in a manner that feels more pop-contemporary and wink-wink existential than such characters usually are in classic noir genre pictures. Unlike Franz and Arthur in Band of Outsiders, Jules and Vincent aren’t regular folks who try to be glamorous movie hit men. They are glamorous movie hit men through and through -- their black-and-white suit-and-tie wardrobe recalls any number of Jean-Pierre Melville’s quietly existential heroes from 1960s noirs like Le Samourai. It’s just that they talk like stoned pop philosophers when they discuss the minutiae of daily life in ways that make such minutiae seem more significant than they really are. Many of Melville’s heroes, by contrast, spoke barely a word. Then there is troubled boxer Butch Coolidge (Bruce Willis), who seems to have walked right out of the 1949 real-time boxing noir The Set-Up, especially since the character is saddled with a plot that recalls similar situations in Robert Wise’s film. And when Butch feels compelled to save an angry Marcellus Wallace (Ving Rhames) from sex-crazed male hicks, the various weapons he examines, before deciding upon a samurai sword as his weapon of choice, implicitly act as representations of the kinds of trash genres -- action, horror, martial arts -- that obsess Tarantino himself.

Yet, as different as their approaches may be, Godard and Tarantino are essentially playing the same game: making films that are heavily intertextual, depending to a certain extent on their -- and our -- knowledge of other works outside of the one we are currently watching. In a way, they are creating both a cinematic meta-context and a community of viewers who get that context.

Choice of genres

Godard and Tarantino’s references to “lower” genres which I referred to above is also a characteristic of postmodernism, and is thus important to articulate here for the purposes to establishing the tradition out of which both directors create in the cinema.

Godard and Tarantino’s references to “lower” genres which I referred to above is also a characteristic of postmodernism, and is thus important to articulate here for the purposes to establishing the tradition out of which both directors create in the cinema.In his essay “Postmodernism and Consumer Society,” Fredric Jameson believes that one of the tenets of postmodernism is the blurring of the lines between high culture and pop culture. As he explains it:

"…[M]any of the newer postmodernisms have been fascinated by that whole landscape of advertising and motels, of the Las Vegas strip, of the late show and Grade-B Hollywood film, of so-called paraliterature with its airport paperback categories of the gothic and the romance, the popular biography, the murder mystery and the science fiction or fantasy novel. They no longer “quote” such “texts” as a Joyce might have done, or a Mahler; they incorporate them, to the point where the line between high art and commercial forms seems increasingly difficult to draw."

This would seem especially appropriate to Tarantino, whose films are almost entirely about his mixing of “texts”; Pulp Fiction, after all, references and borrows from a whole host of films and genres (principally noir films like the aforementioned The Set-Up, but also such diverse sources as Saturday morning cartoons, Saturday Night Fever, even 1960s Godard films like My Life to Live and Band of Outsiders). Even Jackie Brown, arguably Tarantino’s most “down-to-earth” feature, constructs its universe out of remnants of 1970s blaxpoitation flicks (with its star, Pam Grier, its most obvious icon). But keep in mind that Jameson published his article a decade before the Tarantino cult exploded. Godard did this kind of wholesale rummaging of pop culture in many of his ’60s features before Tarantino picked up on it for his films. While many of his ’60s films deconstruct popular American genres -- Breathless, Band of Outsiders (crime drama), A Woman is a Woman (musical comedy), Contempt (Hollywood melodrama), Alphaville (1965, science fiction), Made in U.S.A. (1966, spy thriller), Pierrot le fou (as many genres as possible) -- they also exude the kind of fascination with “low” culture that Jameson is talking about. Appropriate, then, that some early-’60s Godard works like Band of Outsiders and Pierrot le fou are based on supposedly inferior literary material -- a cheap American thriller entitled Fool’s Gold in the case of the former, a Lolita knockoff called Obsession in the case of the latter. Even when Godard credits or quotes “high” literary, artistic or philosophical sources in film -- Pierrot le fou, for example, is loaded with such allusions, from Diego Velázquez to James Joyce -- Godard places them in a distinctly modern context that doesn’t immediately call to mind something that one might initially consider “high” art.

Because both Godard and Tarantino dabble so unreservedly in “lower” genres, and take such an interest in popular culture, many who simply look at the playful surfaces of Band of Outsiders or Pulp Fiction have sometimes perceived the films of both directors as trivial and “fun” at best. As much as they might prefer to play around with the archetypes of crime drama or the musical or whatever, when you see such clichés in their films, they certainly don’t play and feel like any of their sources. Such deconstructions of genre, in addition to embracing a measure of romanticism toward the movie-influenced characters that they sometimes simultaneously debunk, is what intrigues me the most about their work. It is a vivid illustration of the “increasing difficulty” of drawing the line between high and popular art as anything that Jameson points out in his essay.

Because both Godard and Tarantino dabble so unreservedly in “lower” genres, and take such an interest in popular culture, many who simply look at the playful surfaces of Band of Outsiders or Pulp Fiction have sometimes perceived the films of both directors as trivial and “fun” at best. As much as they might prefer to play around with the archetypes of crime drama or the musical or whatever, when you see such clichés in their films, they certainly don’t play and feel like any of their sources. Such deconstructions of genre, in addition to embracing a measure of romanticism toward the movie-influenced characters that they sometimes simultaneously debunk, is what intrigues me the most about their work. It is a vivid illustration of the “increasing difficulty” of drawing the line between high and popular art as anything that Jameson points out in his essay.When it comes to both directors’ self-reflexivity, I think the most important similarity to note is that, because of the distance they instill between the viewer and what is happening onscreen, in their films one often ends up caring less about the ostensible plots and more about other things -- for instance, the artificial, movie-based nature of it all. It is almost as if Godard and Tarantino assume that you are quite familiar with all the conventions of the genres in which they work, that you’ve basically seen it all before, and that there is nothing more to do with genre clichés except to try to mock them or think of them in a new way.

Of course, this begs the question: why are Godard and Tarantino playing this self-reflexive game in the first place?

Band of Outsiders vs. Pulp Fiction

Band of Outsiders vs. Pulp FictionI ended yesterday's installment by asking why Jean-Luc Godard and Quentin Tarantino were interested in self-reflexivity, why they were interested in making movies that deliberately jolted us out of the illusionism inherent in cinema. That question, I believe, is the source of most of the fascinating differences between Godard and Tarantino as film artists, and thus the most worthy of examination. So let me begin this analysis by taking one film by each director and comparing them side-by-side: Godard’s Band of Outsiders and Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction. No, despite their crime-genre nature, both films aren’t exactly equivalent works. Band of Outsiders is, at heart, a simple crime drama about three alienated French youths -- two guys and a girl -- who try to make their humdrum lives better by playacting a robbery, trying to steal money from the girl Odile’s rich aunt.

Pulp Fiction, on the other hand, is a multilayered, three-part postmodern symphony that tells the stories of: 1) Vincent Vega trying to please his boss, Marcellus Wallace, by taking his teasing, voluptuous wife out for an evening; 2) falling-on-hard-times boxer Butch Coolidge trying to elude an angry Marcellus after reneging on a deal to throw a fight; and 3) Vincent and Jules’s desperate attempts to fix the mess Vincent creates when he accidentally shoots a young kid in the head in a car in broad daylight. And even that one-sentence plot summary doesn’t encompass the framing story that surrounds the stories, involving both a young couple’s (Tim Roth and Amanda Plummer) attempts to rob a coffee shop and Jules’s sudden religious awakening spurred on by a near-death incident in the third story. If one film is infinitely more intricately woven than the other, though, both draw from similar sources (principally, the crime genre, but also from musicals and other movies from the 1950s) and both suitably represent what each director is about.

I think I have sufficiently established the ways in which Godard and Tarantino are similar as artists. It’s not just their technique -- long takes, distancing effects, nonlinear storytelling, among other devices -- that is sometimes startlingly similar. Thematically, they also share some striking resemblances. They both obviously have a wide-ranging knowledge of the cinema that occasionally seems to be the substance of their work, so layered with cinematic references are their films from time to time. And within that encyclopedic knowledge is a palpable romantic attitude toward their movie-influenced characters -- a subtle romanticism that sometimes evokes a yearning to live life like a movie.

Yet, as Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote in his 1994 review of Pulp Fiction, “…the differences between what Godard likes and what Tarantino likes and why are astronomical; it’s like comparing a combined museum, library, film archive, record shop, and department store with a jukebox, a video-rental outlet, and an issue of TV Guide.” Of course, Rosenbaum’s implication by making such a comparison is that Godard’s references are much more high-minded -- and thus worth taking more seriously -- than Tarantino’s obvious love for the detritus of pop culture. In trying to maintain at least a smidgen of impartiality, I will simply say that the uses to which these references are put are much more different than they might at first appear, and that a comparison of Band of Outsiders and Pulp Fiction, two stylistically similar postmodern works that end up saying rather different things, will reveal just how different they are.

Yet, as Jonathan Rosenbaum wrote in his 1994 review of Pulp Fiction, “…the differences between what Godard likes and what Tarantino likes and why are astronomical; it’s like comparing a combined museum, library, film archive, record shop, and department store with a jukebox, a video-rental outlet, and an issue of TV Guide.” Of course, Rosenbaum’s implication by making such a comparison is that Godard’s references are much more high-minded -- and thus worth taking more seriously -- than Tarantino’s obvious love for the detritus of pop culture. In trying to maintain at least a smidgen of impartiality, I will simply say that the uses to which these references are put are much more different than they might at first appear, and that a comparison of Band of Outsiders and Pulp Fiction, two stylistically similar postmodern works that end up saying rather different things, will reveal just how different they are.When people look at Band of Outsiders, many, I can imagine, are drawn in immediately by its playful surface. From the jaunty piano music accompanying the rapid-fire montage of close-ups opening the film (one which starts as the classic Columbia Pictures logo fades to black) to its numerous moments of randomness, the film practically becomes all about its digressions as its trio ineptly stage their attempted theft. It is one of Godard’s lighter works, irresistible in its fun-loving mix of crime thriller, slapstick and musical comedy in much the same way as François Truffaut’s Shoot the Piano Player (1960). There is, however, an underlying melancholy and poignancy that runs through much of Godard’s film that is not discussed quite as frequently. Some of that sense of sadness comes from the characters themselves -- as Godard’s dreamily poetic voiceover narration eventually articulates, the thieving efforts of the three main characters are pretty much doomed from the start. But much of the film’s buried melancholy comes simply from its powerful evocation of these characters’ humdrum, working-class lives (further emphasized by both the grayed-out, overcast Paris captured in velvety black and white by frequent Godard cinematographer Raoul Coutard and composer Michel Legrand’s mournful waltzes, harshly undercutting the sprightly nature of that opening piano tune). Outside of the artificial haven that Franz, Arthur and Odile seemingly create together, their home lives are palpably unexciting. Odile lives with her aunt and, at one point, complains about how nothing seems to interest her; Arthur lives with his uncle, and when his uncle finds out about the planned heist, he demands that Arthur give him a cut of the stolen money. (We don’t really see much of Franz in the outside world except for one moment when he’s seen playing basketball with a few friends; perhaps this is in keeping with Arthur’s view of his friend as merely “a good shield” in case of trouble.)

Juxtaposing Godard’s various references and distancing devices along with its documentary-like realism and its sense of impending romantic doom, one gradually realizes that these characters are essentially wishing and trying to live their lives like a B movie -- with Godard himself seemingly egging them on with his narration, imparting a poetry to the events of the film that deliberately doesn’t quite connect with the resolutely mundane nature of what is happening onscreen. That this harsh reality eventually -- fatally, in Arthur’s case -- catches up to all three of them at the end indicates not only what Godard is attempting in this film, but also what he’s essentially going for in many of his other ’60s features. He seems to be exploring the fine and disappointing line between movie fantasy and reality, and often concluding, with a disillusioned wince, that movie fantasy simply isn’t compatible with social or political reality. (In this regard, Godard’s A Woman is a Woman -- a so-called “neorealist musical” set in working-class Parisian surroundings that isn’t technically a musical at all, even if it sure feels like a classic American musical comedy -- is also a representative work.) At one point in Band of Outsiders, Godard, in trying to explain Franz’s thoughts as he and the two other characters do their Madison thing, comes up with this line: “He wondered if the world is becoming a dream or if the dream is becoming the world.” A more fitting summation of Godard’s stylistic and thematic obsessions would be hard to imagine.

Juxtaposing Godard’s various references and distancing devices along with its documentary-like realism and its sense of impending romantic doom, one gradually realizes that these characters are essentially wishing and trying to live their lives like a B movie -- with Godard himself seemingly egging them on with his narration, imparting a poetry to the events of the film that deliberately doesn’t quite connect with the resolutely mundane nature of what is happening onscreen. That this harsh reality eventually -- fatally, in Arthur’s case -- catches up to all three of them at the end indicates not only what Godard is attempting in this film, but also what he’s essentially going for in many of his other ’60s features. He seems to be exploring the fine and disappointing line between movie fantasy and reality, and often concluding, with a disillusioned wince, that movie fantasy simply isn’t compatible with social or political reality. (In this regard, Godard’s A Woman is a Woman -- a so-called “neorealist musical” set in working-class Parisian surroundings that isn’t technically a musical at all, even if it sure feels like a classic American musical comedy -- is also a representative work.) At one point in Band of Outsiders, Godard, in trying to explain Franz’s thoughts as he and the two other characters do their Madison thing, comes up with this line: “He wondered if the world is becoming a dream or if the dream is becoming the world.” A more fitting summation of Godard’s stylistic and thematic obsessions would be hard to imagine.When she enthusiastically reviewed Band of Outsiders for The New Republic in 1966, Pauline Kael explained Godard’s method this way:

"An artist may regret that he can no longer experience the artistic pleasures of his childhood and youth, the very pleasures that formed him as an artist … But, loving the movies that formed his tastes, he uses this nostalgia for old movies as an active element in his own movies. He doesn’t, like many artists, deny the past he has outgrown; perhaps he hasn’t quite outgrown it. He reintroduces it, giving it a different quality, using it as shared experience, shared joke."

Kael might as well have been talking about Tarantino with that quote, because he puts his obvious love of movies -- from gangster flicks to blaxploitation fare, from Godard to Seijun Suzuki, etc. -- front and center in his own films as much as Godard did in his early work. And both directors are fascinated with the idea of making movies that make you aware that you are watching a movie. But ultimately, there is a chasm of difference between them, and one can see it when comparing Band of Outsiders and Pulp Fiction side-by-side.

For one thing, there’s the dialogue. Tarantino is known for his verbal wit, and his dialogue in Pulp Fiction is undeniably fresh and inventive: from discussions about the differences between the names of burgers in France and America to an argument about the erotic potential of foot massages, Tarantino comes up with absurdist lines that are, at their best, not only clever for their own sake but also revealing of the character uttering those lines. As clever as his dialogue undeniably is, though, there really is no mistaking it for the speech of characters who live in a recognizable real world, at least not compared to the (semi-improvised) dialogue spoken by the characters (as opposed to the voiceover narration) in Band of Outsiders, which occasionally makes mild gestures toward a rough kind of poetry (Franz to Arthur and Odile: “A minute of silence can be a long time; a real minute of silence can take forever”) but more often stays deliberately flat and functional. Of course, though, that is part of Godard’s point in the film: he presents us with ordinary characters dreaming of something beyond themselves.

For one thing, there’s the dialogue. Tarantino is known for his verbal wit, and his dialogue in Pulp Fiction is undeniably fresh and inventive: from discussions about the differences between the names of burgers in France and America to an argument about the erotic potential of foot massages, Tarantino comes up with absurdist lines that are, at their best, not only clever for their own sake but also revealing of the character uttering those lines. As clever as his dialogue undeniably is, though, there really is no mistaking it for the speech of characters who live in a recognizable real world, at least not compared to the (semi-improvised) dialogue spoken by the characters (as opposed to the voiceover narration) in Band of Outsiders, which occasionally makes mild gestures toward a rough kind of poetry (Franz to Arthur and Odile: “A minute of silence can be a long time; a real minute of silence can take forever”) but more often stays deliberately flat and functional. Of course, though, that is part of Godard’s point in the film: he presents us with ordinary characters dreaming of something beyond themselves.Tarantino’s Pulp Fiction characters -- a collection of slacker hit men (Jules, Vincent), threatening mob bosses (Marcellus Wallace), femme fatales (Mia Wallace) and laconic men of violence (Butch) -- already seem to have achieved that transcendence: they all seem to bear the full weight of movie history upon them even as some of them talk like dorm-room philosophers with a little too much free time on their hands. After a while, it doesn’t really matter what they say -- their words are usually not important to the main storylines anyway. It’s all about how they express themselves. In other words, it’s all about style. And with dialogue as self-consciously stylized as Tarantino’s in Pulp Fiction, the effect is to lend the entire dialogue-driven movie an aura of hyper-stylization that silences whatever concessions to realism -- mostly through cinematographer Andrzej Sekula’s fairly straightforward rendering of certain settings (in color, of course, as opposed to Raoul Coutard’s black and white) -- Tarantino half-heartedly makes. You are consistently aware that you’re watching a movie with characters created expressly for it speaking lines of dialogue that you probably won’t hear anywhere else -- you aren’t necessarily watching people, but signs. (In some ways, Tarantino’s Jackie Brown is an exception to his norm: it is intermittently suffused with the kind of nostalgia and melancholy perfectly befitting a touchingly mournful look at old age, and thus has more of the kind of humdrum dialogue of Band of Outsiders, except with a distinctly Tarantinian flavor. It’s as if, for Tarantino, the word “aging” attached to “icon” -- which Pam Grier certainly was in 1970s blaxploitation fare -- is grounds for more serious reflection than you find in many of his other works to date. Kill Bill, Vol. 2, the much quieter of the two Kill Bill films, also shares some of that seriousness and could conceivably be read as a contemplation of the price of revenge. Death Proof, meanwhile, may mostly lack the reflective quality of Jackie Brown, but it may be the closest Tarantino has come to mixing a serious genre study with his distinctive sense of playfulness).

There’s another matter, though, regarding Pulp Fiction, and that is what the film is actually about outside of its acute sense of personal style. Here is where things get tricky: is it really about anything else other than its narrative games and stylistic bravura?

There’s another matter, though, regarding Pulp Fiction, and that is what the film is actually about outside of its acute sense of personal style. Here is where things get tricky: is it really about anything else other than its narrative games and stylistic bravura?The film’s concluding monologue -- a speech delivered by a newly-spiritually-enlightened Jules to a thieving man-and-woman couple who impulsively decide to rob a coffee shop -- suggests a concern on Tarantino’s part with the idea of redemption even for this bunch of lowlifes, a deliverance from their trivia-talking, coldly violent ways. There is something to that, it must be said. In some ways, all three storylines deal with different forms of salvation for the various characters: Vincent is saved from the hell of having to deal with Marcellus’ wrath if Mia died on him from a cocaine overdose; Butch -- who had reneged on a deal to throw a boxing match and won it instead, killing his opponent in the process -- redeems himself in the eyes of an angry Marcellus when he rescues him from further sodomy at the hands of a band of Confederate male hicks; and Jules decides he has been given a second chance at saving his soul when he fails to get killed by a barrage of gunfire.

Yet there is a sense of glibness to Tarantino’s approach in tackling such weighty themes as spirituality and redemption that somehow makes Jules’ final speech (as chillingly delivered as it is by Samuel L. Jackson) less a profound revelation than a convenient (though undoubtedly effective) structural way of winding down this particular picture. It’s as if Tarantino was simply going for an effect rather than dealing with spirituality in any particular depth. Actually, that is perhaps inaccurate: Tarantino is certainly dealing with spirituality, but he does it almost entirely through pop-culture terms. The most revealing moment in this regard is almost a throwaway. Jules has just told Vincent that, because of his personal spiritual awakening, he is going to quit the hit man life and “walk the earth.” When Jules asks what he means by that, he immediately says, “You know, like Caine in Kung Fu” -- referring to the old 1970s cult TV series which chronicled the adventures of a Shaolin monk (played by David Carradine, who of course would later be cast by Tarantino as an assassin boss in his Kill Bill features) on the run in America. In the film’s own pop culture-obsessed terms, Jules may well be throwing out such a reference simply so Vincent will understand what he means; he may not actually mean that he intends to live a lifestyle like Caine’s. But the line strikes me as indicative of Tarantino’s approach to content in Pulp Fiction: he consistently deals with “big” issues in terms of old movies and pop culture. As Slant Magazine critic Ed Gonzalez has written about the film, “Much like his characters, the director can only live by engaging cinema.”

Both Band of Outsiders and Pulp Fiction thus establish the essences of both directors enough to begin a more complete discussion of their differences in terms of their wider body of work. In lieu of a mere disorganized list of contrasts, however, tomorrow I will undertake such a discussion in terms of exploring the idea of parody versus pastiche.

Both Band of Outsiders and Pulp Fiction thus establish the essences of both directors enough to begin a more complete discussion of their differences in terms of their wider body of work. In lieu of a mere disorganized list of contrasts, however, tomorrow I will undertake such a discussion in terms of exploring the idea of parody versus pastiche. Parody and Pastiche

Parody and PasticheWhen one thinks of parody, one might immediately think of blitzkrieg spoofs like the Mel Brooks movie satires (Blazing Saddles, Young Frankenstein, High Anxiety, Spaceballs, etc.) or the 1980 airline-disaster-movie takedown Airplane! But those deliberately lowbrow laugh-a-minute joke-fests represent only one kind of parody.

In general, parody has a critical intent: it tries to deconstruct and then mock outdated or plain silly conventions, and it does so often by adopting those same conventions. As many might agree, only if an artist understands those conventions can he even think about demolishing them through parody effectively. Parody, though, does not necessarily have to be funny/ha-ha comedy -- it could also be funny/strange (to borrow terms coined by Andrew Sarris) in the sense that it is trying to render as odd and ridiculous certain artistic sacred cows, whether that entails merely a cliché or an entire outdated genre. Blazing Saddles, for instance, took on the Western genre as its target, while Airplane! toyed mercilessly with the conventions of the disaster genre that was seemingly in vogue through a good part of the 1970s. Of course, to be able to satirize both Westerns and disaster epics with any effectiveness, the filmmakers had to understand and, at the very least, look like a standard-issue Western or disaster epic (Airplane!, for instance, took this a step further and based its entire plot on a 1957 airline disaster flick entitled Zero Hour). Robert Stam defines it in this way:

"Parody, one might argue, emerges when artists perceive that they have outgrown artistic conventions. Man parodies the past, Hegel suggested, when he is ready to dissociate himself from it. Literary modes and paradigms, like social orders and philosophical epistemes, become obsolescent and may be superseded. When artistic forms become historically inappropriate, parody lays them to rest."

Considering that definition, one could legitimately consider many of Godard’s genre deconstructions as parodies. Not all of them are comedies -- Alphaville is a serious picture in addition to being a deadpan spoof of science-fiction films; the resolutely austere and experimental Contempt wears the guise of a lurid color melodrama whose dark humor is dwarfed by its sheer scale and gloominess -- but they all share that deconstructive intent, taking a critical look at cinematic classics.

Considering that definition, one could legitimately consider many of Godard’s genre deconstructions as parodies. Not all of them are comedies -- Alphaville is a serious picture in addition to being a deadpan spoof of science-fiction films; the resolutely austere and experimental Contempt wears the guise of a lurid color melodrama whose dark humor is dwarfed by its sheer scale and gloominess -- but they all share that deconstructive intent, taking a critical look at cinematic classics.As referential, self-referential and movie-obsessed as Godard is, however, Tarantino is not a parodist in the same manner. Tarantino may reference all sorts of films and genres and cultural artifacts, but he does not do so in a spirit of satire or even a light ribbing. He’s merely referencing them.

Thus we come to the concept of pastiche. To put it simply, it’s parody without the critical intent. As Jameson defines it:

"Pastiche is, like parody, the imitation of a peculiar or unique style, the wearing of a stylistic mask, speech in a dead language: but it is a neutral practice of such mimicry, without parody’s ulterior motive, without the satirical impulse, without laughter, without that still latent feeling that there exists something normal compared to which what is being imitated is rather comic. Pastiche is blank parody, parody that has lost its sense of humor…"

Tarantino certainly has not lost his sense of humor in his films. But his humor does not necessarily grow out the feeling that the director is spoofing genre constructions; his absurdist dialogue is simply a clever way to make clichéd characters feel fresh. In nearly every other respect, “pastiche” is a legitimate way of describing most of his films. He cobbles together elements of a dizzyingly vast array of genres and styles, but the spirit behind his references is not mockery: the intent is often simply to affectionately play around with such genres and styles rather than to reflect on or critique them. What is the point, for instance, of revolving part of the story of Kill Bill: Vol. 2 around the grave of a woman named Paula Schultz other than the fact that the name refers to a 1968 comedy entitled The Wicked Dreams of Paula Schultz? Or what exactly is Tarantino intending when he whimsically decides to place a black-and-white back-projection townscape -- like something right out of a ’40s noir -- behind Butch and a female cab driver as he is escaping from the scene of his victory fight/murder?

Those are but two of a countless number of references in Tarantino’s work, but the point here is: to this movie-watcher, there doesn’t seem to be a clear deconstructive point to Tarantino’s references as there often is with Godard. There is a big difference, for instance, between, say, Godard using esteemed German director Fritz Lang to play himself in his Contempt and Tarantino using former Japanese martial arts star Sonny Chiba to play a sword-maker and trainer in Kill Bill: Vol. 1. Godard may be as huge a fan of Lang as Tarantino is of Chiba, but in the context of his rigorous and complex examination of filmmaking, the film business, and personal relationships, Lang stands out as an icon of the cinematic old guard, “the only uncorrupted and incorruptible figure” in Contempt, as Jonathan Rosenbaum has said. Chiba’s character, by contrast, seems to have importance only in context of the film’s plot (he trains the Bride for her eventual showdown with O-Ren Ishii, one of the five assassins responsible for trying to kill her at her wedding). Otherwise, it seems that the only reason he’s in the film, one could conclude, is because the movie geek inside Tarantino deeply desired to have this martial arts icon in his tribute to martial-arts movies.

Those are but two of a countless number of references in Tarantino’s work, but the point here is: to this movie-watcher, there doesn’t seem to be a clear deconstructive point to Tarantino’s references as there often is with Godard. There is a big difference, for instance, between, say, Godard using esteemed German director Fritz Lang to play himself in his Contempt and Tarantino using former Japanese martial arts star Sonny Chiba to play a sword-maker and trainer in Kill Bill: Vol. 1. Godard may be as huge a fan of Lang as Tarantino is of Chiba, but in the context of his rigorous and complex examination of filmmaking, the film business, and personal relationships, Lang stands out as an icon of the cinematic old guard, “the only uncorrupted and incorruptible figure” in Contempt, as Jonathan Rosenbaum has said. Chiba’s character, by contrast, seems to have importance only in context of the film’s plot (he trains the Bride for her eventual showdown with O-Ren Ishii, one of the five assassins responsible for trying to kill her at her wedding). Otherwise, it seems that the only reason he’s in the film, one could conclude, is because the movie geek inside Tarantino deeply desired to have this martial arts icon in his tribute to martial-arts movies.Ultimately, the difference between Godard’s art and Tarantino’s is the difference between a philosopher of the movie image and an obsessive movie fan. It is necessary for Godard to utilize his Brechtian distancing devices because he is trying in part to explore and deconstruct the power of movie images in all of their forms: from the look of a movie icon on a poster (the poster of Bogart in Breathless) to the familiar images and associations evoked by Hollywood movie clichés. From the use of familiar movie-musical tropes -- the snatches of high-spirited music, Raoul Coutard’s brilliant Technicolor palette -- to cast a different light on what might otherwise be a mundane character drama in A Woman is a Woman, to the characters of Band of Outsiders playacting at being hoods, Godard frequently takes apart Hollywood genre conventions and questions how they get their meaning, and whether that meaning has any relation to ordinary lives at all. (Even a later ’60s Godard film like Two or Three Things I Know About Her is essentially tackling the same subject -- it’s just that, this time, he is exploring the image and how it acquires meaning in an industrialized, consumerist society rather than in the context of other movies.)

Tarantino may be Godard’s equal in exposing the artifice of his cinematic constructions, but he doesn’t so much deconstruct genre conventions as use them as a source of fun. Whereas Godard is concerned with exposing the reality underlying movie images, Tarantino is very much in love with the images they create. In other words: Tarantino lacks the critical distance Godard maintains in many of his films. That is why Tarantino uses real gangsters in Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, for example, as opposed to regular people who yearn to be movie gangsters, as Godard’s protagonists in Breathless and Band of Outsiders are. While it is true, as critic Fernando F. Croce points out in his review of Kill Bill: Vol. 2, “Tarantino in Kill Bill raises the characters to a level of mythical movie lore before twisting them to reveal flesh and blood,” the important point to emphasize for the purpose of my thesis is that Tarantino conceives his characters as images from the start before trying to reveal the human beings underneath, while Godard goes the opposite way. Tarantino doesn’t deconstruct so much as reconstruct from available parts.

Tarantino may be Godard’s equal in exposing the artifice of his cinematic constructions, but he doesn’t so much deconstruct genre conventions as use them as a source of fun. Whereas Godard is concerned with exposing the reality underlying movie images, Tarantino is very much in love with the images they create. In other words: Tarantino lacks the critical distance Godard maintains in many of his films. That is why Tarantino uses real gangsters in Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction, for example, as opposed to regular people who yearn to be movie gangsters, as Godard’s protagonists in Breathless and Band of Outsiders are. While it is true, as critic Fernando F. Croce points out in his review of Kill Bill: Vol. 2, “Tarantino in Kill Bill raises the characters to a level of mythical movie lore before twisting them to reveal flesh and blood,” the important point to emphasize for the purpose of my thesis is that Tarantino conceives his characters as images from the start before trying to reveal the human beings underneath, while Godard goes the opposite way. Tarantino doesn’t deconstruct so much as reconstruct from available parts.Tarantino’s approach, of course, has led some critics to accuse him of triviality -- of making empty popular entertainments that signify little except that the director has seen and absorbed a lot of movies. Fair enough, although I would submit that a closer look at the nuances of his films would reveal that they are hardly empty. Tarantino is taking on genuinely big subjects in his films: Reservoir Dogs and Pulp Fiction deal, in different degrees, with honor among criminals; Pulp Fiction adds a hint of pop spirituality into the mix; Jackie Brown is a leisurely tribute to the ’70s blaxploitation genre that also suggests the melancholy of old age in front of and behind the camera; the two Kill Bill films, taken together, could be seen as a revenge epic that charts one woman’s transformation from vengeance-thirsty warrior to flawed human being; and I would submit that the relatively small-scale Death Proof is Tarantino’s bid to consider, in his own way, the sexual politics inherent in the slasher-movie genre. For someone who claims, both in public and through his films, to simply be having fun while making movies, he also clearly has his sights on serious topics. But Tarantino’s style is what seems to throw his critics: his filmmaking is so viscerally delirious, his references are so multitudinous, and his dialogue and visual style are so overtly stylized and exaggerated that it sometimes fools people into not taking his films seriously as anything other than a movie fan’s tribute to his passions.

Perhaps it is the general absence of politics -- which could itself be a political position, apathy -- that jars some of his critics. None of his films deal much with real-world events; you won’t find any trace of political commentary or satire in Tarantino’s films. In fact, in none of Tarantino’s movies is there much of a reference, either visually or verbally, to a world outside either movie history or the borders of the movie frame. All of his films seem to take place in self-contained universes of his own movie-influenced imagination, and his only gestures to recognizing a reality outside the proscenium arch come from his use of real-life settings and his relatively straightforward way of capturing those settings on film. In other words, with the arguable exceptions of Jackie Brown and Death Proof (and even in those films topicality isn’t much of an issue), Tarantino’s films are, above all, fantasies based on the movies that he has seen and loved, and Tarantino doesn’t try to pretend that his films are anything more realistic than that.

Perhaps it is the general absence of politics -- which could itself be a political position, apathy -- that jars some of his critics. None of his films deal much with real-world events; you won’t find any trace of political commentary or satire in Tarantino’s films. In fact, in none of Tarantino’s movies is there much of a reference, either visually or verbally, to a world outside either movie history or the borders of the movie frame. All of his films seem to take place in self-contained universes of his own movie-influenced imagination, and his only gestures to recognizing a reality outside the proscenium arch come from his use of real-life settings and his relatively straightforward way of capturing those settings on film. In other words, with the arguable exceptions of Jackie Brown and Death Proof (and even in those films topicality isn’t much of an issue), Tarantino’s films are, above all, fantasies based on the movies that he has seen and loved, and Tarantino doesn’t try to pretend that his films are anything more realistic than that.Godard, however, has politics in abundance throughout his films from the 1960s -- hardly surprising considering both the politically tumultuous environment in which his films arose and the politically- and philosophically-aware French culture in which Godard was brought up (both are environments I will explore in some depth later). Even in films like A Woman is a Woman and Band of Outsiders that don’t place much emphasis on French politics or global affairs, Godard throws in little hints of politics here and there to shake us out of our genre-induced stupor. Thus it is jarring to hear, at one point, Arthur reading a news item at one random moment in Band of Outsiders about Hutus massacring Tutsis in Rwanda (how prophetic in light of the ethnic cleansing that took place in that country in 1994), or to see Jean-Paul Belmondo’s character in A Woman is a Woman walking around wearing a French tricolor armband on his right arm. Sure, Godard did take early cracks at political works, as in the relatively austere 1960 film Le Petit soldat (dealing ambivalently with the problematic methods used by the rebel FLN during the Algerian war for independence from France) and the deliberately grimy 1963 anti-war film Les Carabiniers (a film-about-war-films which also could profitably be considered a black comedy in its bleak view of humanity amidst the absurdities of war).

It was after Pierrot le fou in 1965, however -- which features heavy, critical references to the Vietnam War -- that politics seeped into Godard’s films with a vengeance until, by the time he completed Weekend (and even before then, with films like La Chinoise), he had thrown off the shackles of movie storytelling altogether and started making explicit political tracts. (This gradual but unmistakable shift in his filmmaking style coincided with his participation in the events of May ’68 and his growing belief in Maoism; later he, Jean-Pierre Gorin and others would form the Dziga Vertov group, dedicated to “making films politically.”) Thus, Masculin féminin features a main character, Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who is politically confused (although he doesn’t admit it to us); La Chinoise interrogates one particular group’s fascination with Maoism; and Weekend, of course, takes his fascination with politics to some kind of savagely satirical, bitter zenith.

It was after Pierrot le fou in 1965, however -- which features heavy, critical references to the Vietnam War -- that politics seeped into Godard’s films with a vengeance until, by the time he completed Weekend (and even before then, with films like La Chinoise), he had thrown off the shackles of movie storytelling altogether and started making explicit political tracts. (This gradual but unmistakable shift in his filmmaking style coincided with his participation in the events of May ’68 and his growing belief in Maoism; later he, Jean-Pierre Gorin and others would form the Dziga Vertov group, dedicated to “making films politically.”) Thus, Masculin féminin features a main character, Paul (Jean-Pierre Léaud), who is politically confused (although he doesn’t admit it to us); La Chinoise interrogates one particular group’s fascination with Maoism; and Weekend, of course, takes his fascination with politics to some kind of savagely satirical, bitter zenith.Tarantino, it must be said, has only made five feature films (and his most satirical effort, his screenplay for Natural Born Killers, was transformed by its eventual director Oliver Stone into something quite different from what Tarantino apparently had in mind), so perhaps it is too early to see whether he will eventually shift from the loving, self-contained genre pastiches he has made so far to something more seriously worldly and political. But, even in his earlier works, Godard evinced hints of a politically minded sensibility. Perhaps Tarantino’s only overtly political act so far in his young career was his choice of Michael Moore’s anti-George W. Bush documentary Fahrenheit 9/11 for the Palme d’Or at Cannes in 2004 (a film which, incidentally, Godard publicly denounced, stating that Moore “doesn’t distinguish between text and image”). Very little in his movies suggests political reflection as much as reflections of cinema history and popular images -- a fact that understandably leads people to write off Tarantino’s art as trifling and unserious. I do not believe, however, that Tarantino’s concern for elucidating the humanity underneath genre icons (or lack of that concern) makes him less of an artist than Godard. He may be a different kind of artist, but not necessarily an inferior one. This leads me to my final point.

When it comes to interpreting or evaluating a work of art, a common tendency is to consider it strictly on its own terms, as a work unto itself, without considering the personal or social circumstances surrounding the creation of that work. Arguably, it is easier to evaluate a work that way, because there is no extra baggage to consider. However, to look at it strictly from such a formalistic standpoint, and thus to neglect historical or social context, is to neglect not only important facets of how art is often created, but also of how we as audience members and art consumers receive and consider that work. Something inspires an artist to create a work, and while ultimately the interpretation of a finished work of art is in the eyes and minds of the viewers, an attempt at interpretation that disregards the surroundings in which the work was born makes for a rather superficial analysis of it.

An example of what I mean: whether or not you consider recent films-about-9/11 like Paul Greengrass’s United 93 or Oliver Stone’s World Trade Center to be genuine works of art or not, one cannot deny that, however universal both films aspire to be (and the controversial United 93, by blurring specifics and going for a strict docudrama approach, seems to aim for some kind of rather perverse universality), they derive at least some of their power from this troubled political and emotional environment in which we currently find ourselves. Same for the spate of political Hollywood films released last year, including films like George Clooney’s Good Night, and Good Luck, Stephen Gaghan’s Syriana, and Steven Spielberg’s Munich. Many interpreted Good Night, and Good Luck’s visual evocation of 1950s black-and-white television and verbal references to actual speeches delivered by Edward R. Murrow -- “We cannot defend freedom abroad by deserting it at home,” he says in one of his famous broadcasts -- as Clooney’s way of drawing a parallel between Senator Joseph McCarthy and President George W. Bush; likewise, Spielberg made comparisons to the war in Iraq inevitable in Munich when he concluded the film -- which dealt with the efforts of an underground state-sponsored Israeli group to avenge the deaths of their fellow Israelis at the 1972 Munich Olympic games at the hands of the Black September Palestinian terrorist group -- with a shot of the Twin Towers in the landscape. What I am trying to suggest here is that, try as one might, one cannot, and should not, try to separate art from the historical or even personal contexts from which a particular work emerges.

This idea of the importance of context underlies my ultimate contention that Jean-Luc Godard and Quentin Tarantino, as different as they are, are still, in some ways, essentially similar filmmakers who came out of very different circumstances, both personally and historically, and that those circumstances should be taken into consideration when comparing both of their works side-by-side.